de Uniter miercuri, 12 iulie 2023

Text publicat de Maria Zărnescu în Critical Stages/Scènes critiques

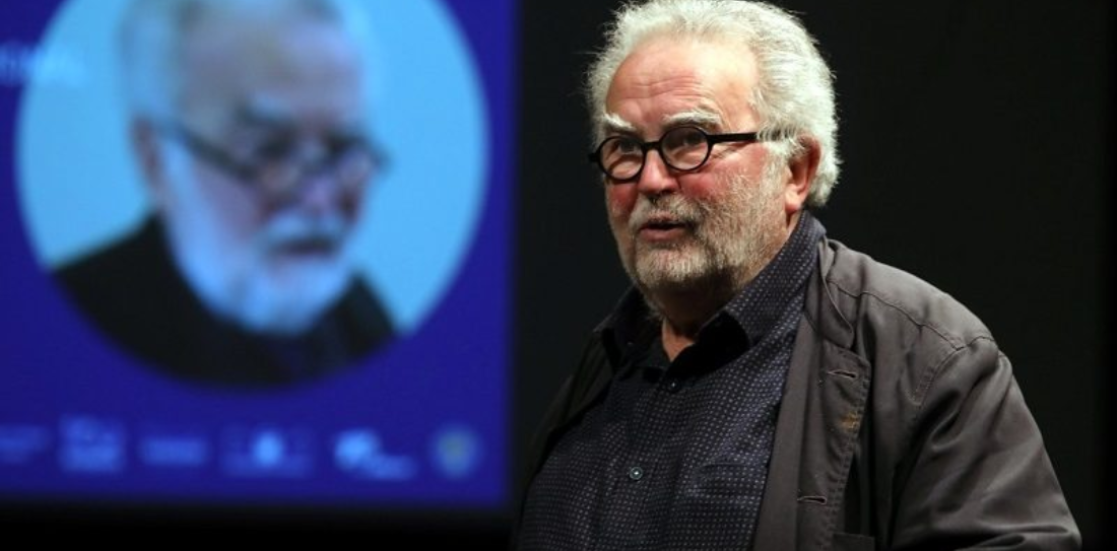

As an informed spectator, witness-critic, essayist and playwright, committed educator, godfather of countless theatre festivals, tireless and inquisitive traveler, mentor and friend, Georges Banu was a true citizen of the world. Born in Romania on June 22, 1943, he graduated from high school in Buzău, and began acting studies at the Theatre and Film Institute I.L. Caragiale in Bucharest, later graduating in 1968 with a specialization in Theatrology-Filmology. He completed his PhD in Aesthetics, at the University in Bucharest, in 1973; his doctoral thesis was entitled Modes of Theatrical Communication in the 20th Century.[1] He worked as Teaching Assistant, at the Faculty of Theatre, and published in the Romanian press of the time. On 31 December 1973, New Year’s Eve, he arrived in France, where he began his teaching career at the University Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3, working from 1974 to 2012, and subsequently named Professor Emeritus of Theatre Studies. He taught and worked at numerous universities both within and beyond Europe, several of which have granted him the title Doctor Honoris Causa.

Georges Banu held a number of positions of responsibility in the International Association of Theatre Critics AICT-IATC, having served as Secretary General, 1986-1992, President, 1996-2001, and more recently, Honorary President. He also held the positions of Artistic Director (Experimental Academy of Theatres), President (Europe Theatre Prize), and Secretary General (Union of European Theatres).

Georges Banu was General Editor of the series Le Temps du Théâtre, published by Actes Sud, and Co-Director of the magazine Alternatives théâtrales. In 2014, the French Academy granted him the Grand Prix de la Francophonie, and, on three occasions, he was awarded as an author for Best French Book, with his scholarly contributions Bertolt Brecht. Le petit contre le grand (1981), Le théâtre, sorties de secours (1983), and Le Rouge et l’Or, une poétique du théâtre à l’italienne (1989). He was also an Honorary Member of the Romanian Academy, and won the Excellence Award in 1993, followed by the President’s Award of the Romanian Association of Theatre Professionals UNITER in 2001. Written in both Romanian and French, his work has been translated into Italian, German, Spanish, Russian, Hungarian, Slovakian and Polish.

Georges Banu published numerous books and essays devoted to European directors, in particular Peter Brook, Klaus Michael Grüber, Giorgio Strehler, Antoine Vitez, and Ariane Mnouchkine, and he collaborated with directors Luc Bondy, Yanis Kokkos, Krzysztof Warlikowski and Patrice Chéreau, Thomas Ostermeier and Krystian Lupa on their productions staged in France. After 1990, he was a key presence in the most important theatre festivals in Romania, such as The National Theatre Festival in Bucharest, The International Meetings and Interferences International Theatre Festival in Cluj, the Shakespeare International Festival in Craiova and the Sibiu International Theatre Festival, where he was engaged as a dedicated patron, an active presence, an informal adviser and most importantly, as a friend. Georges Banu would often quip that he could only write about friends, friends in life or beyond death.

Thus, Shakespeare and Chekhov were his friends and guardian spirits. Notre théâtre: La Cerisaie (Actes Sud, 1999) and Le Théâtre de Anton Tchekhov (Ides et Calendes, 2016), as well as the anthology Shakespeare, le monde est une scène: métaphores et pratiques théâtrales (Gallimard, 2009) and Les Récits d’Horatio: portraits et aveux des maîtres du théâtre européen (Actes Sud, 2021) are in fact guidebooks for deciphering the two playwrights’ works, as well as the corresponding performances. In 1997, Georges Banu won the UNESCO Award, together with Jacques Renard, for the best documentary film about theatre, Tchekhov – Le Témoin impartial.

In Shakespeare’s play, Hamlet admires and praises his friend, Horatio, for his virtues, self- control and strength of character. As he lay dying, Hamlet assigned his friend a mission to tell his story. “Let me speak to th’yet unknowing world/ How these things came about…” Georges Banu took up a similar mission in the world of theatre, to which he dedicated himself for more than half a century. In his words, “Towards the final, unavoidable hour, I cast myself in Horatio’s role, as the ending life is Hamlet himself, my prince!… The Theatre has not yet turned to ashes, but burning embers whose extinguishing I try to delay.”[2] Many of Banu’s writings may be defined as informed viewer’s diaries, born from “the long coexistence with the opera and with the essays that the stagings represent: a spectator’s diary, a travelogue, neither systematic, nor didactic.”[3]

Georges Banu has always distinguished between professor and educator, deeply involved in the international academic world, while at the same time recognizing the virtue of pleasure as an indispensable preamble to pedagogy. His relationship to the theatre was both active and selfless, with neither dogmatic programs nor arrogant distance, always situated between the theatre and the university, which he viewed as the most legitimate position for an arts education. He aimed, “not only to give, but also to know how to receive. Pedagogy in theatre is extremely complicated, as one cannot teach directly what is essential; rather, that which is essential must be perceived. A combination between certainty and uncertainty would be ideal. There is no composite sketch for the ideal professor, there are only great educators who teach you and reveal their truth to you, but who also lead you towards your truth.”[4] He surrounded himself with young people whom he esteemed, and the feeling was mutual.

Entire generations of students and professionals eagerly read his essential books about theatre and art: L’acteur qui ne revient pas (1986), Les cités du théâtre d’art. De Stanislavski a Strehler (2000), La scène surveillée, miniatures théoriques (2008), Amour et désamour du théâtre (2013), Les voyages du comédien (2012), L’inaccompli ou le défi du théâtre (2016), and Le théâtre et l’esprit du temps (2021). Georges Banu wrote a trilogy about theatre and painting, Le Rideau (1997), L’Homme de dos (2000) and Nocturnes (2005), and a series of books consisting of La Nuit (2004), L’Oubli (2005) and Le Repos (2009). He also edited Théâtre et opéra: une mémoire imaginaire (1990), Le Théâtre testamentaire (1991), Le Théâtre de la nature (1992), L’Est désorienté (2000), Le Corps travesti (2007) and Extérieur cinéma (2009).

Although he was known for openly sharing his experience, both professional and personal, in his books and lectures, Georges Banu never completely revealed himself. For him, the theatre seems to have been his own Cherry Orchard, a dramatic image of unyielding transformation. After the era of Anton Chekhov, the change in society was catastrophic: the communist revolution took the place of an expected modernity. Georges Banu left socialist Romania at the very time when the feeble cultural enlivenment installed at the end of the 1960s was going to be completely erased by Ceausescu’s so-called cultural revolution. His destination was France, the place from which enlightenment has come to us, at least in the last two centuries. He had hoped to find a point of entry to a career in the freedom offered by a capitalist society, and while he was thoroughly committed to his goal, the specifics remained unclear.

Georges Banu lived in Paris and committed himself to the theatre, and his passion for theatre was sustained throughout his entire life. His tribute to the City of Lights, including some of his most intimate commentaries, is found in the trilogy My Personal Paris. Published by Nemira Publishing House, Bucharest, his trilogy included Urban Autobiography (2013), House of Gifts (2015), and The Family of 18 Rivoli (2016). At the side of his friend, Mihaela Marin, an expert in photography of theatre and opera, the author reconstructed his vibrant life in stories and images accessible to all categories of readers, both the professional / academic as well as the lay audience.

It is almost impossible to capture the entire personality of Georges Banu;[5] it is equally difficult to write impersonally about Georges, or George, in Romanian, or Biţă, as he was known among friends. There are those rare individuals who can somehow merge their professional notoriety with a natural social grace; any interaction with Georges Banu, whether in person or through correspondence, immediately placed you in a circle of trust, much like the interaction constructed during primary acting exercises which requires a great deal of trust between the person in the middle and the members of the circle. But once there, the person in the middle becomes a point on a wavefront, from where, according to Huygens’ discovery in physics, one can set off a new wavefront. Yet still, even if the circle of trust were to bring you closer to the center, or, on the contrary, move you toward the periphery, you would never feel fully in control of the truth, in its entirety.

A life dedicated to scholarly research might have a monastic quality in itself, a mission, a faith that would push any worldly interests to a secondary level; Georges Banu’s life, however, was not like that. He was a man of the world, enjoying the theatre and his travels as evidence of life, not aspiring to asceticism. Educated and groomed in the spirit of journeys, Georges Banu would often quote the title of Milan Kundera’s book, Life Is Elsewhere. He displayed an enviable restless mobility; his often-cited catchword, “No more time to run out of time” seemed to be his motto. He enjoyed the warmth of human relationships, and he was one of those few who still understood and valued a postal card, infinitely more human and personal than the more efficient digital messages. We knew his address by heart: 18 Rue de Rivoli, Paris. In turn, he wrote to his close friends, in life and beyond: “Dear Great Anonymous, dear William, you have allowed me to overcome the non-loving of theatre. You have forbidden me to be stranded in scepticism! May you enjoy sweet rest and know that it is also due to you that many of us are still alive today. P.S. I have not left my address because I do not expect an answer. The satisfaction and the courage for having dared to write to you are gratification enough.”[6]

Georges Banu wrote until the last moments of his life. He usually ended his messages in the closing phrase “with hope,” although in his final years he began to use the expression “with scepticism” instead. It was not a sign of pessimism, but rather an expression of visionary lucidity. The death and illnesses of people close to him, the fire at Notre-Dame Cathedral, the pandemic, the war in Ukraine and, regrettably, the scandals in the Romanian theatre had deeply and systematically saddened him. He always hoped that humour would save us, but towards the end he felt more and more anxious and lonely.

Georges Banu left us at the beginning of this year, 2023, on a January night in Paris. This year, on the 23rd of June, he would have reached eighty years of age. They say that eight is a sacred figure, representing the cosmic balance, the balance between Heaven and Earth, the sign of a reclining infinity. May your life be eternal in the peace of the world, dear Sir!

* * *

The lines which follow below have joined the countless recollections written by theatre professionals from both Romania and the rest of the world. The Senate of UNITER created a book of condolences[7] and special editions of cultural magazines were published: the THEATRE today (UNITER & Cultural Foundation, Camil Petrescu, Nr. 1-2, 2023) and SpectActor (National Theatre Marin Sorescu, Craiova, Nr. 1, January-April, 2023). All the future theatre festivals to be held in Romania will be dedicated to the memory of Georges Banu, a true professional and a dear friend.

Our Honorary President was one of the truly great minds of global theatre in this or any generation. For generations of theatre critics affiliated with the International Association of Theatre Critics, Banu was a thoughtful, incisive mentor who inspired new ways of thinking about theatre even as he brought attention to artists who might otherwise have been overlooked. Georges Banu’s extraordinary capacity for work, for thought and for analysis raised theatre criticism to a kind of art form and lifted the study of the human experience to new heights. We are unlikely to see someone pass our way again and deliver such a deep cultural impact.

Jeffrey Eric Jenkins, President of the International Association of Theatre Critics

The death of Georges Banu left the theatre community impoverished. May you rest in peace! Your work will continue to inspire thousands of people. What you have left behind is a true gift for the coming generations!

Savas Patsalidis, Editor-in-chief of Critical Stages/Scènes critiques,

the journal of the International Association of Theatre Critics

Georges Banu was a titan of the theatre, a wise man, a man of wit, seeking artistic pleasure, a sensualist of the show of life and art.

The Romanian Association of Theatre Professionals UNITER

We are grieving and plunged in sad thought; we are not prepared for this parting! We are not prepared for the disappearance of Horatio, a character that, in his last years, Biță Banu was personally assuming, as a metaphor of friendship and togetherness, which make the act of criticism meaningful. Beyond condolences, beyond words, beyond whatever might still be said, a tragic breeze irremediably stirs the waves of this absence…

Oana Cristea Grigorescu, Mihaela Michailov, Călin Ciobotari,

The National Festival of Theatre curators

Endnotes

[1] The French summary of the thesis was presented, for reading, to Bernard Dort, well known critic and professor at Sorbonne Nouvelle, who commented at the time: “The text you gave me confirms that you read the same books as we did here in Paris!” After this, Dort became Banu’s doctoral supervisor in France. The original thesis was published in 2011 under the title Forms of Theatre in the Century of the Renewal (Nemira Publishing House). The book comes as a natural continuation of the so-called Bible of the Romanian theatrologists, The Art of the Theatre by Michaela Tonitza-Iordache and Georges Banu (Romanian Encyclopedic Publishing House, 1975).

[2] Georges Banu, Horatio’s Stories, Tracus Arte Publishing House, Bucharest, 2021 (trad.aut.)

[3] Georges Banu, The Cherry Orchard, Our Theatre, Nemira Publishing House, Bucharest, 2011 (trad.aut.)

[4] Georges Banu delivered a lecture entitled The Art of the Educator-Professor on 21st November 2013, at UNATC, when he received the Diploma of Excellence as a Key personality of the world theatre and the Romanian School of Theatrology on his 70th birthday. The complete text of the lecture was published in Concept magazine vol. 7/ nr. 2, UNATC Press, December 2013 (trad.aut.).

[5] In Romania, several books have been dedicated to him: Georges Banu in dialogue with Mircea Morariu, The Second Life: Comments and Confessions About Theatre (Cheiron, 2016); The Travels and the Horizon of Theatre. A Homage to Georges Banu (coordinated by Catherine Naugrette, Nemira, 2013); Close to the Stage. Essays and Testimonies (coordinated by Iulian Boldea and Ştefana Pop-Curşeu, Curtea Veche, 2013); Silvian Floarea, Georges Banu. Portrait in an Art Gallery (Junimea, Iaşi, 2020); and two volumes of the important cultural journal The 21st Century – Georges Banu. Our Contemporary (vol. I, 7-12, 2019, vol. II, 1-6, 2020, Romanian Writers Union and the 21st Century Cultural Foundation).

[6] Georges Banu, Letter to Shakespeare, yorick.ro, 19 April 2016 (trad.aut.)